There are a few points on the subject of shame that I would like to expand upon. The first comes from the novel “Brideshead Revisited”, which demonstrates, completely contrary to the Modernist, post-Christian, Bergoglian anti-church heresy, how shame is a medicinal mercy.

If we can self-generate shame without having to have it applied from the exterior, then so much the better. But for many people, the shaming must be generated, at least initially, externally. This is a function of charity – true charity, not the mindless platitude consisting of indifference yielding permissiveness, or in giving people “free stuff”, or just simply “what makes them happy”. No, true charity is joy in the existence of another and thus a focused desire that that person make it to heaven. Full stop.

If you are not familiar with Brideshead Revisited, the context is easily explained. Set between the World Wars in England, Julia is civilly divorced from yet sacramentally married to Rex, and is shacking up with Charles, who is also civilly divorced. Charles and Julia make a real cute couple and “love” each other (inasmuch as people who express their “love” for one another do so by knowingly flagellating and crucifying Christ in exchange for having an orgasm, can actually be said to love one another in any honest sense of the word.)

[Bridey has just announced his engagement to Beryl Muspratt, a widow with three children. Julia asks why he hasn’t brought Beryl to Brideshead to meet her]

Lord Brideshead ‘Bridey’: [pompously] You must understand that Beryl is a woman of strict Catholic principle, fortified by the prejudices of the middle classes. I couldn’t *possibly* bring her here. It is a matter of indifference whether you choose to live in sin with Rex or Charles or both – I have always avoided enquiry into the details of your ménage – but in no case would Beryl consent to be your guest.

Julia Mottram: Why, you pompous ass!

[Julia walks out of the room, holding back tears]

Charles Ryder: Bridey! What a bloody offensive thing to say to Julia.

Lord Brideshead ‘Bridey’: [coldly] It was nothing she should object to. I was merely stating a fact well known to her.

Long story short, Julia eventually breaks off her affair with Charles and lives at home, alone for the rest of her life, reconciled to Our Lord through His Holy Church, namely through the Sacrament of Confession.

Beryl Muspratt, painted by all of the protagonists as a villain, ugly, frumpy, judgmental, and emblematic of “everything wrong with the Church”, even though she is never directly seen in the novel, only discussed and quoted a few times by others, is the most heroic figure in the novel. She is reported as always being kind to Julia, but unwavering in her defense of the Truth, in this case the Truth about marriage and the Sixth Commandment. Thus, she could never consent to being a guest in the home of a woman – even her own sister-in-law – whom she knows to be Living in Sin, because to do so would ratify the sin itself, ratify the torture and murder of God Himself, and also REDUCE the likelihood that Julia (and Charles) would repent, correct their situation, and die confessed and in a state of grace, be that five minutes hence, or five decades. Beryl cannot coerce Julia or anyone else to love God, but she can and rightly does apply medicinal shame to Julia in the hopes that the pain of that shame might lead Julia to stop torturing and killing Christ, and thus utterly rejecting His Love in favor of having orgasms with a cute guy, and in so doing, damning herself to hell.

It is precisely because Julia was made to feel PROFOUNDLY ASHAMED by Beryl refusing to enter her home that Julia set out on the road to repentance. If Beryl had been a typical Novus Ordo “church of Nice” Kathy-zombie of today and sought to “encounter” Julia with the “tender caresses” of FAUX MERCY, manifested by indifference to Julia and her mortally sinful lifestyle, Julia would have been EDIFIED AND CONFIRMED IN HER SIN, and thus would not have repented and corrected. And neither would Charles – both would have been lost to hell, in all likelihood.

Interestingly, Bridey, the older brother, is revealed by his own words as being “indifferent“, and thus it is BRIDEY, with his lack of charity for the soul of his own sister, that is the most villainous character in this particular scene. But even then, he concludes by stating that Julia has no right to object to the statement of facts which she already knows – namely the Sixth Commandment and Our Lord’s words in Matthew 19. The only thing Julia has a right to object to or be hurt by is Bridey, her own brother, declaring that he is “indifferent” to her sin, and thus to the fate of his own sister’s soul, not to mention Charles’ soul. That’s it. And Beryl Muspratt is indeed the heroine of the novel.

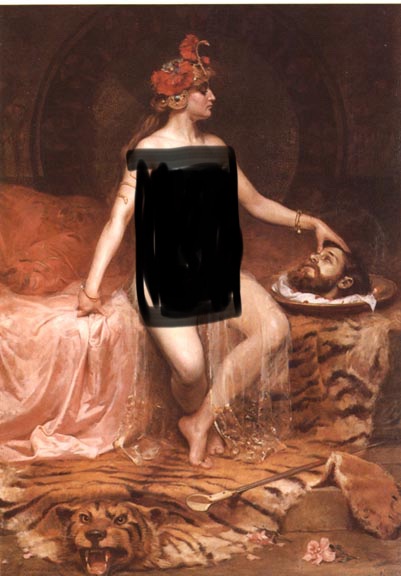

Finally, here is a very powerful image of Salome with the severed head of John the Baptist. It was technically Salome’s mother, Herodias, who was condemned by John for her illicit marriage and thus agitated her daughter to request John’s execution, but the symbolism of the shameless, sinful woman smugly looking down at John’s head is the point. Note the rehearsed air of power, the heavily practiced pose of defiance and victory, her features hard and joyless. Now look at The Baptist’s face. Even in death, his face is soft and quick, still emoting a genuine CHARITY. He almost looks to be making eye contact with the woman, still trying to convince her to repent. Now look back at the woman. Look now at how weak and shallow and PATHETIC she is compared to him, essentially naked, save her gaudy headdress and jewelry; as transparent and superficial as her gauze girdle. She fancies herself a queen, but she’s just a sad gutter denizen, wallowing and relishing in her own sin.

This image is a profound allegory of our post-Modern, post-Christian, feminist culture.

St. John the Baptist, pray for us.

Salome, Pierre Bonnaud, ARSH 1865-1930, Musée Hebert

Salome, Pierre Bonnaud, ARSH 1865-1930, Musée Hebert