Our Father, Who art in heaven, hallowed be Thy Name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us. And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Amen.

PATER NOSTER, qui es in caelis, sanctificetur nomen tuum. Adveniat regnum tuum. Fiat voluntas tua, sicut in caelo et in terra. Panem nostrum quotidianum da nobis hodie, et dimitte nobis debita nostra sicut et nos dimittimus debitoribus nostris. Et ne nos inducas in tentationem, sed libera nos a malo. Amen.

One of the great jailbreaks in history. Excerpted from HERE.

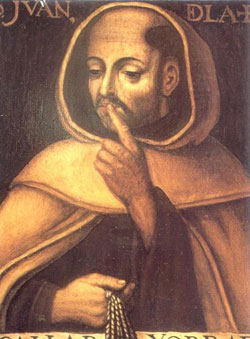

It was at Toledo that St. John went through the greatest and most dramatic crisis of his life. He underwent a severe test of his courage, endurance and faith. He was caught in the vortex of a dispute between the Carmelites of the Mitigated Observance and the Carmelites of the Reform. … St. John of the Cross was taken prisoner in December, 1577, from his chaplain’s house at the Convent of the Incarnation in Avila and brought to Toledo…

He was imprisoned in the monastery in Toledo in a room ten feet by six, with a very small slit high in the wall being his only source of light. The room was really nothing but a large closet. Here St. John was locked in for nine months, suffering from the cold in the winter and the stifling heat in the summer. When he was brought out, it was to take his meal of bread and water and sometimes sardines, kneeling in the refectory, and to hear the upbraidings of the Prior. After the meal on Fridays, he had to bare his shoulders and undergo the circular discipline for the space of a Miserere. Each person present struck him in turn with a lash. St. John bore the scars of these beatings throughout his life.

A change in jailers after six months brought a more lenient friar to be his keeper. But he was torn by doubt as to what was God’s Will: Should he try to escape, or was it the will of God for him to die here? His searching prayer was answered by the conviction that he should escape. So he began to plan. While the others were at table, the more lenient young Father, Juan de Santa Maria, allowed St. John to help clean the cell. This included the liberty of walking down the corridor outside the room onto which his prison closet opened in order to empty the night pail. The jailer had also given St. John a needle and thread to mend his clothing. He tied a small stone to the thread and measured the distance to the ground from a window in the corridor. Back in his cell, he sewed his blankets together and found that they would, if used as a rope, reach to within 11 feet of the ground – close enough to permit a jump. Little by little he had also loosened the screws in the padlock outside the cell. On the night he planned to escape, two visiting friars happened to be sleeping in the room outside. They awoke when the padlock fell when St. John shook it, but they went back to sleep again, their sleepy eyes perhaps being closed by a wide-awake angel.

St. John stepped between the friars and silently let himself out through the window and down on his improvised rope. Had he landed two feet farther out from the building, he would have fallen to the rocky banks of the Tagus River below. He next found himself in a court surrounded by walls; he was almost ready to give up, but he finally succeeded in climbing one of the walls and was able to drop into an alleyway of the city. After daybreak, he found the convent of the Discalced Carmelite nuns, who sheltered him and later found a temporary refuge for him in the Hospital of Santa Cruz, very close to the monastery from which he had escaped. The friars from the monastery had come to the convent looking for him while he was there, and now little knew that the emaciated, nearly dead object of their search was being nursed back to life not a stone’s throw away.